Explore the World's Best Ideas

Join today and uncover 100+ curated journeys from 50+ topics. Unlock access to our mobile app with extensive features.

A Waste of Time

A universal language will always be an unattainable dream. For centuries, idealists and crackpots tried to invent a global tongue, but even Esperanto never took off. Marina Yaguello explains why.

The comedian Sacha Baron Cohen, in his stage persona as the dim-witted interviewer Ali G, once asked Noam Chomsky if a person could simply invent a new language from scratch. The renowned linguist gave him short shrift: ‘You can do it if you like and nobody would pay the slightest attention to you because it would just be a waste of time.’

17

146 reads

A Single Primordial Tongue

Throughout history, however, a motley array of eccentrics has done just this, and received a fair bit of attention.

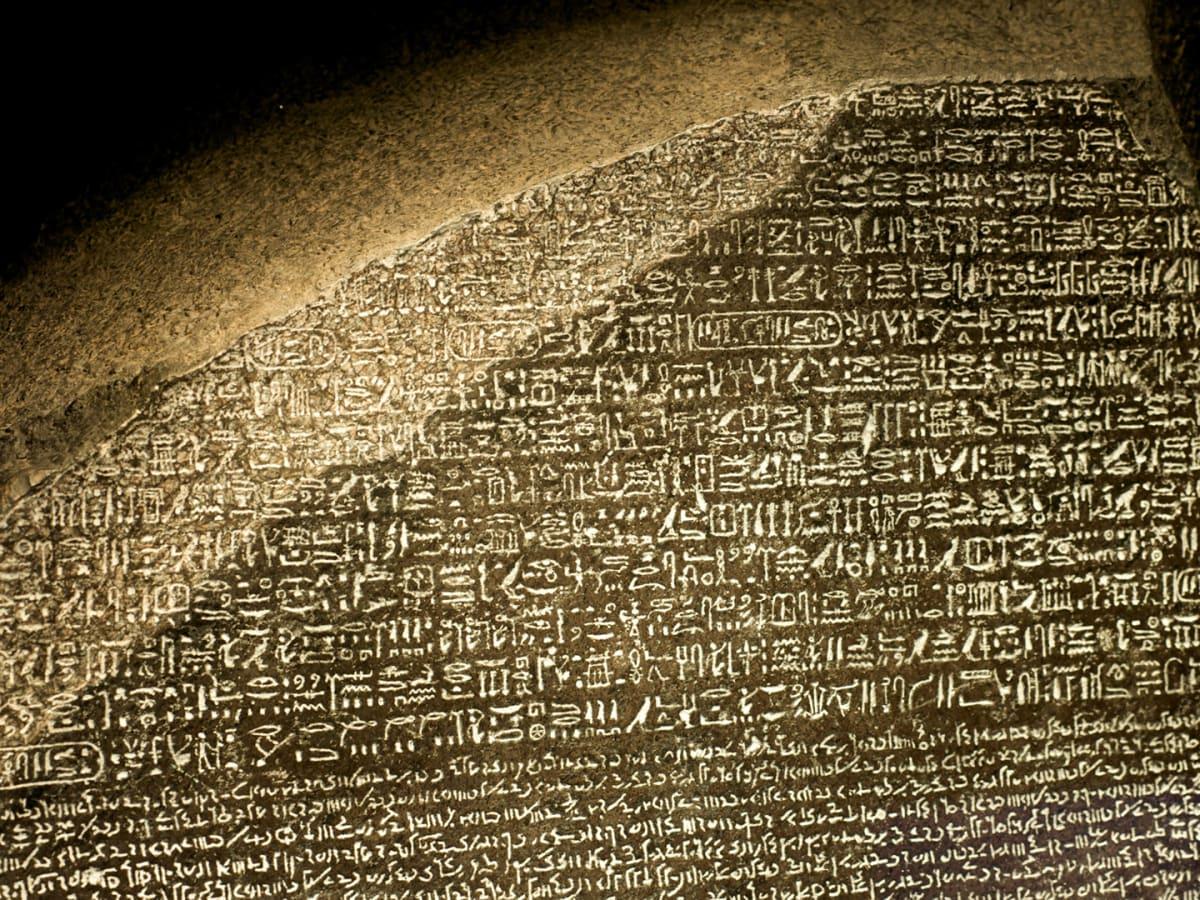

Originally published in 1984 but only now translated into English, Marina Yaguello’s fascinating survey of constructed languages revisits the history of two distinct but interlinked — and equally fanciful — intellectual projects: the attempt to retrace the origins of all world languages to a single primordial tongue; and the dream of constructing a universal language that would eventually supplant all others.

15

107 reads

To Invent a Language

You don’t have to be mentally disturbed to invent a language, but it helps: glosso-maniacs, paranoiacs and megalomaniacs are well represented in this pantheon.

Yaguello’s archetypal innovator is a tragicomic obsessive reminiscent of Edward Casaubon in George Eliot’s Middlemarch:

“We can picture the logophile in a study crammed with books; all around lie vast quantities of information yet to be collated, classified, listed and indexed on countless tables and cards. A delirium of naming, taxonomical madness, has seized this solitary figure…”

15

72 reads

Cranks and Fantasists

Cranks and fantasists abound. The 12th-century abbess Hildegard of Bingen, inventor of the earliest known artificial language, lingua ignota, claimed it came to her in a divine vision.

One of several amusing tidbits in Imaginary Languages involves the 19th-century Swiss medium Hélène Smith, who purported to communicate with Martians during her seances.

When it was pointed out that the grammatical and syntactic structures of her ‘Martian’ were uncannily similar to those of French, she went away and composed another extraterrestrial tongue, which she called ‘Ultra-Martian’.

15

48 reads

Esperanto

Its lexicon was more clipped and its syntax deliberately mangled so as not to resemble French. These endeavours took on a political dimension in the modern era.

Utopians of the late 19th and early 20th centuries — among them L.L. Zamenhof, the inventor of Esperanto — believed a universal language could usher in a new age of international peace and brotherhood.

Two world wars, and the rise of English to something like a global lingua franca, put paid to such hopes.

15

39 reads

The Language as a Superstructure

The chimera of a universal language could also be enlisted for reactionary ends, as demonstrated by the career of the Georgian-born Soviet philologist Nikolai Marr.

He peddled a vulgar Marxist theory that language is a superstructure mirroring society’s economic base, and the unification of different languages into a single tongue is the logical endpoint of national development.

Though discredited by fellow linguists, his ideas were endorsed by Stalin in the 1930s to lend intellectual legitimacy to his imperialist Russification agenda.

15

27 reads

Imaginary Languages

Some very fine imaginary languages are to be found in works of fiction. The people in Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) speak a blend of Greek and Persian called — imaginatively — Utopian; in Francis Godwin’s Man in the Moone (1638), a lunar-dwelling population communicate via a musical language in which each utterance forms a melody; in Alexander Bogdanov’s Red Star (1908), all the inhabitants of Mars speak the same Martian tongue; the novels of J.R.R. Tolkien feature fictional dialects inspired by Anglo-Saxon; ---->

16

31 reads

A Crucial Flaw

------->the Newspeak in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) is probably the best known fictional example of a ‘philosophical language’ — one specifically designed to demarcate the boundaries of acceptable thought.

Yaguello, a professor of linguistics at the University of Paris VII, notes a crucial flaw in many invented languages.

The hermetic neatness to which their creators aspire — seeking to marry ‘harmony, eloquence, straightforwardness, logic, clarity of reference, musicality, symmetry, regularity and economy’ — contrasts markedly with the messy reality of natural tongues.

16

27 reads

A Neurotic Impulse

She highlights the excessive schematism of Volapük, a would-be universal language devised by a German Catholic priest in 1879, which ‘contains moods not often found in world languages — for example, the operative and dubitative’.

It’s no coincidence that the most enduring constructed language, Esperanto, is also among the least rigid; the fact that it has spawned a number of variants is ‘a sign of vitality’.

If the desire to engineer new languages originated in a certain innate drive — a neurotic impulse to arrange and codify that resides in all of us to a greater or lesser extent —-->

16

23 reads

Impossible as Perpetual Motion

------>i t is in the nature of language to resist such limitations. Flexibility and mutability are essential; flux is a feature, not a bug.

‘A universal language,’ writes Yaguello, ‘is as impossible as perpetual motion.’ But when did futility ever get in the way of a good idea? The catalogue of invented tongues is more than just a cultural curio: it’s a monument, really, to the hubristic folly of human intelligence.

Originally published at The Spectator

15

22 reads

IDEAS CURATED BY

Antonio Gallo's ideas are part of this journey:

Learn more about books with this collection

How to break bad habits

How habits are formed

The importance of consistency

Related collections

Discover Key Ideas from Books on Similar Topics

5 ideas

Language as Evidence

Victoria Guillén-Nieto, Dieter Stein

7 ideas

How the Laws of Physics Lie

Nancy Cartwright

2 ideas

Semantic Change: How Words Evolve Over Time

blog.csoftintl.com

Read & Learn

20x Faster

without

deepstash

with

deepstash

with

deepstash

Personalized microlearning

—

100+ Learning Journeys

—

Access to 200,000+ ideas

—

Access to the mobile app

—

Unlimited idea saving

—

—

Unlimited history

—

—

Unlimited listening to ideas

—

—

Downloading & offline access

—

—

Supercharge your mind with one idea per day

Enter your email and spend 1 minute every day to learn something new.

I agree to receive email updates