Explore the World's Best Ideas

Join today and uncover 100+ curated journeys from 50+ topics. Unlock access to our mobile app with extensive features.

The Minds Of Animals Were Disregarded Earlier

Until rather recently, philosophers and scientists have been reluctant to grant a mind to any nonhuman entity. Feelings and emotions, hope and pain and a sense of self were deemed attributes that separated us from the rest of the living world.

To René Descartes in the 17th century, and to behavioural psychologist BF Skinner in the 1950s, other animals were stimulus-response mechanisms that could be trained but lacked an inner life. To grant animals “minds” in any meaningful sense was to indulge in a crude anthropomorphism that had no place in science.

22

322 reads

The Reason Of Animal Behaving Like Humans

If other animals behave like us, that’s no basis to assume that they do so for the same reasons and with the same experiences and mental representations of the world. But as countless careful experiments like this study of pigs reveal ever more about the inner world of animals, there comes a point where it looks far more contrived to suppose that their behaviour just happens to look like ours in all kinds of ways while differing utterly in its explanation. Maybe, instead, they have minds that are not really so different after all.

23

259 reads

A New Look At Animal Minds

The challenge, then, becomes finding a way of thinking about animal minds that doesn’t simply view them as like the human mind with the dials turned down: less intelligent, less conscious, more or less distant from the pinnacle of mentation we represent.

We must recognise that the mind is not a single thing that beings have more or less of. There are many dimensions of mind and the space of minds has multiple coordinates, and we exist in some part of it, a cluster of data points that reflects our neurodiversity.

22

213 reads

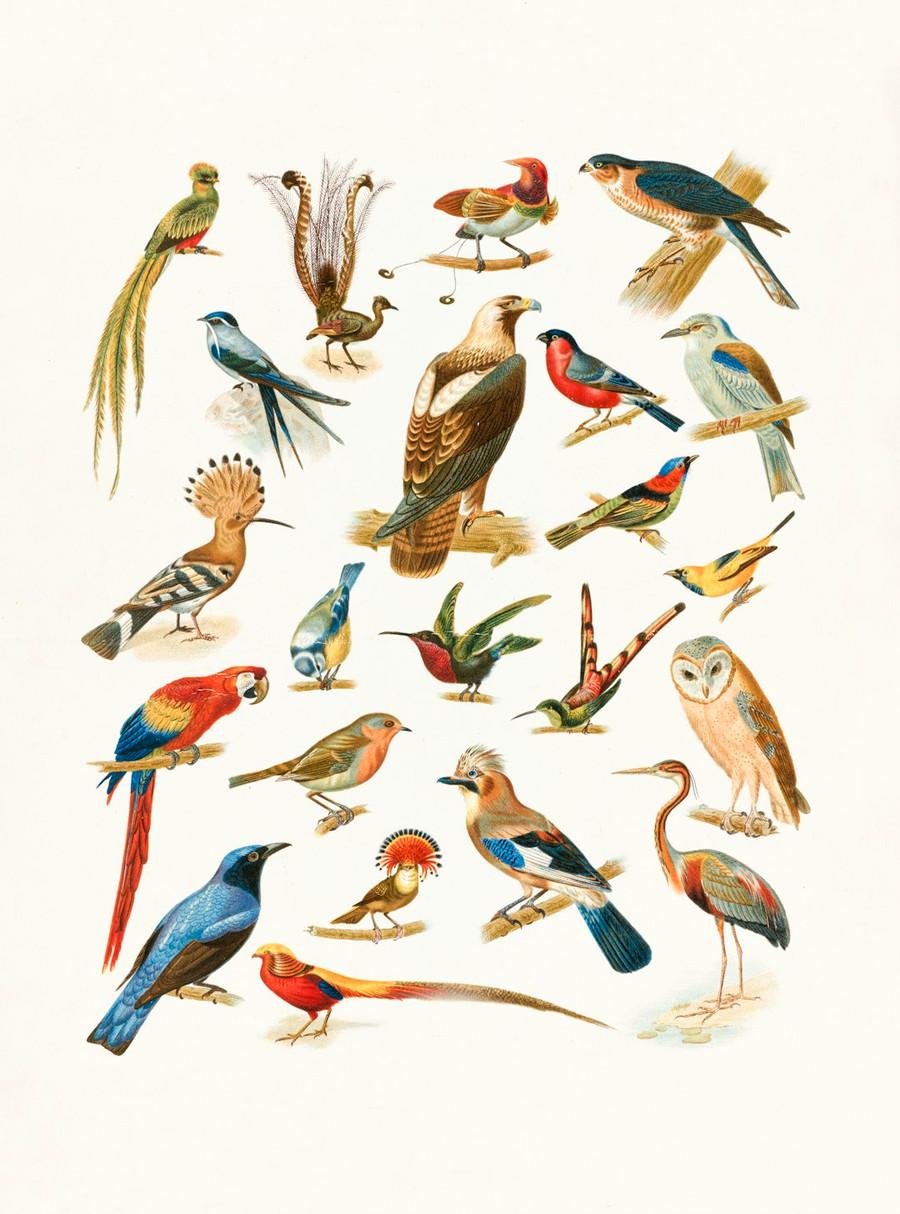

The Birds

Birds’ minds are scattered widely in mind-space, their differences and specialities tremendously varied. Some birds excel at navigation, others at learning complex songs or making elaborate nests.

Scrub jays are expert food storers, able to stash hundreds of caches around their habitat and find them all flawlessly, returning first to the most perishable items.

They are cunning: cache thieving is common, and the birds might employ deceptive measures such as returning soon after depositing a store to move it to another location – but only if they know they were observed while caching it.

23

194 reads

Animals Using Tools

We award pride of place in the hierarchy of bird minds to tool-using species, especially corvids (crows, ravens, rooks). The most masterful of them is the New Caledonian crow of the south Pacific, which will design and store custom-made hooks for foraging, and even make tools with multiple parts. Among animals, great apes, dolphins, sea otters, elephants and octopuses are the only others known to use tools. The challenge is to figure out which qualities of mind corvids bring to bear on the task.

25

153 reads

Birds Are Self-Aware

It was long assumed that the anatomy of the bird brain (lacking a neocortex) is too different from ours to support any conscious experience, but recently those differences have been found to be less pronounced. How do you test, though, if another animal has a sense of self? One approach is to see if it shows an ability to assess its own state of knowledge: can a bird “look into” its own mind and acknowledge what it doesn’t know? Recent experiments with crows suggest they can.

21

151 reads

Bees That Play Football

Lars Chittka of Queen Mary University of London and his colleagues have trained bees to manipulate a small ball into a hole at the centre of the “pitch” for a sugary reward. Bees can train one another in the task, and can find better solutions than their demonstrator: they don’t blindly follow rules but adapt them to the circumstances.

It is also seen that the honeybee conveys information about a distant food source to its hive members by dancing.

24

148 reads

The Optimistic Bee

Bees can be trained to feel good or bad using flowers: blue ones carry a sugar reward, green ones don’t, but will a bee interpret an ambiguously blue-green flower optimistically or pessimistically? Again, behaviour seems to be coloured by experience: bees that have just been given an unexpected sugar treat seem more inclined to optimism, as though put in a good mood. We can’t know if the behaviour is accompanied by a “feeling” – but machines don’t do stuff like this.

21

132 reads

The Octopus Is Really Smart And Has Feelings

The octopus is “probably the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien.” Octopuses interact with us, apparently with neither fear nor aggression. But in contrast to a dog or a chimpanzee, it’s hard to fathom what the agenda might be. They are great problem-solvers: they unscrew jars, navigate mazes in the murky gloom of the seabed, and fuse bright laboratory lights with jets of water. They seem playful – but who knows, really, what the antics are for?

21

139 reads

The Amazing Creatures Of The Sea

The octopus has a similar number of neurons as a dog, but instead of being mostly collected in a central brain they are distributed throughout the body in a ladder-like network. There is a centralised brain in the head, but more than half of the nervous system is in the arms, gathered into clusters called ganglia that seem to operate largely autonomously: the arms do things of their own accord while the brain watches, perhaps as if observing another creature.

24

126 reads

On Plants Being Sentient

Biopsychism supposes that every living being from bacteria up has sentience of a sort.

Plants don’t have a nervous system, or even neurons. But their cells, like many non-neural cells, do communicate with one another electrically, and there’s evidence that cellular channels in plants called phloem can transport not only sugars but also electrical pulses. Some plants show distinctly animal-like behaviour: witness the carnivorous jaws of the Venus flytrap, which even displays a primitive ability to “count” the number of impulses it senses before closing on an insect.

23

129 reads

The Sunflower Follows The Sun

Plants can sense and respond to stimuli, as when flower heads move to track the progress of the sun across the sky. The South American “sensitive plant” Mimosa pudica, a member of the pea family, folds its leaves when touched and displays a kind of learning called habituation, where it eventually ignores a repeated stimulus that proves harmless. Pea plants can be trained in an almost Pavlovian fashion to associate a neutral signal such as the flow of air with a beneficial signal such as light.

24

123 reads

A Sentient Universe

Conceiving a universe of possible minds can discourage human hubris, and advises erring on the side of generosity in considering the rights and dignity of other beings. But it also enables a literally broad-minded view of what other minds could exist. Mindedness needn’t be a club with rigorously exclusive entry rules. We might not (and may never) agree about whether plants, fungi or bacteria have any kind of sentience, but they show enough attributes of cognition to warrant a place somewhere in this space.

24

129 reads

AI Consciousness Is More Than Just Computing Speed

To suppose that something like artificial consciousness will emerge simply by making computer circuits bigger and faster is, as one AI expert put it to me, like imagining that if we make an aeroplane fly fast enough, eventually it will lay an egg. Computers and AI are taking off in the “intelligence” direction of mind-space while gaining nothing on the “experience” axis. If we want AI to be more human-like, many experts believe we will need explicitly to build human qualities into it – which in turn requires that we better understand what those are and how they arise.

24

115 reads

Aliens Are Not Going To Be Like We Imagine Them

Most of our fantasies about advanced alien intelligence suppose it to be like us but with better tech. That’s not just a sci-fi trope; the scientific search for extraterrestrial intelligence typically assumes that ET carves nature at the same joints as we do, recognising the same abstract laws of maths and physics. But the more we know about minds, the more we recognise that they conceptualise the world according to the possibilities they possess for sensing and intervening in it; nothing is inevitable.

We need to be more imaginative about what minds can be.

23

117 reads

IDEAS CURATED BY

CURATOR'S NOTE

Animals, birds and plants are sentient beings with feelings, memory, adaptiveness and emotions.

“

Jason Z.'s ideas are part of this journey:

Learn more about scienceandnature with this collection

How to make rational decisions

The role of biases in decision-making

The impact of social norms on decision-making

Related collections

Similar ideas

4 ideas

Your brain thinks – but how?

theconversation.com

1 idea

Hey! A Bee Stung Me! (for Kids)

kidshealth.org

7 ideas

Human intelligence: have we reached the limit of knowledge?

theconversation.com

Read & Learn

20x Faster

without

deepstash

with

deepstash

with

deepstash

Personalized microlearning

—

100+ Learning Journeys

—

Access to 200,000+ ideas

—

Access to the mobile app

—

Unlimited idea saving

—

—

Unlimited history

—

—

Unlimited listening to ideas

—

—

Downloading & offline access

—

—

Supercharge your mind with one idea per day

Enter your email and spend 1 minute every day to learn something new.

I agree to receive email updates