On The Surprising History Of Cheerfulness And Its Subtle Power

Curated from: aeon.co

Ideas, facts & insights covering these topics:

20 ideas

·2.72K reads

16

Explore the World's Best Ideas

Join today and uncover 100+ curated journeys from 50+ topics. Unlock access to our mobile app with extensive features.

Power Dwells With Cheerfulness

“Power dwells with cheerfulness,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson. Though we often think of cheerfulness as the opposite of power, as an insincere urge to liven things up, Emerson knew it to be a resource of the self, a tool for shaping our emotional lives that can help to relocate us in the social world and link us to community. At the present time, as we confront wave after wave of bad news sweeping the planet, cheerfulness is worth our consideration.

30

507 reads

Cheerfulness Is A Modest Power, But A Power All The Same.

With cheerfulness, we see a rise in emotional energy, a sudden uptick in mood. It is fleeting or ephemeral, in that it comes and goes. But we can control it. We can “cheer up”, just as we can “calm down”. As the English philosopher Robert Burton put it in The Anatomy Of Melancholy (1621): “expect a little … Cheer up.” Burton’s advice to “expect a little” reminds us that cheerfulness is a modest power. But, as Emerson knew, it is a power all the same.

25

325 reads

Cheerfulness Is Largely Elective: We Choose It; We Can Manage It

Perhaps it is because of the modesty of cheerfulness that philosophers have largely overlooked it. They tend to focus on more dramatic emotions such as anger and melancholy, viewing human emotional life as a battleground of unconscious drives or overwhelming passions. The classic example of the man ruled by passion is the Greek hero Achilles. Overcome by his wrath toward Agamemnon, Achilles refused to join his fellow Greeks in the war against Troy, thereby betraying his own duty as Greece’s greatest warrior. Unlike wrath, cheerfulness is largely elective. We can manage it.

24

259 reads

The Relationship Of Cheerfulness And Melancholy

It is no accident that the English philosopher Robert Burton mentions cheerfulness in a book about melancholy. In much writing about emotion, cheerfulness is presented as the antidote to the dark emotions of the melancholic. Medical thinkers up into the 19th century assumed that the human body was governed by the circulation of fluids, or humours. Melancholy, for example, arose from an excess of black bile, while certain stimulants were understood to counter melancholy and generate cheerfulness. Other doctors argued that it was possible to stimulate cheer chemically.

26

190 reads

The Relationship Of Cheerfulness And The Body

Medical thought and practice aside, it is clear that cheerfulness is deeply linked to the body, and, in particular, the face. Indeed, it begins in the face and moves inward. As the French writer Germaine de Staël pointed out at the beginning of the 19th century, when you take on a cheerful expression, no matter what the state of your soul, your cheerfulness moves into the self: “the facial expression penetrates, bit by bit, what one experiences.” The interior of the self is changed by the power of cheer.

25

157 reads

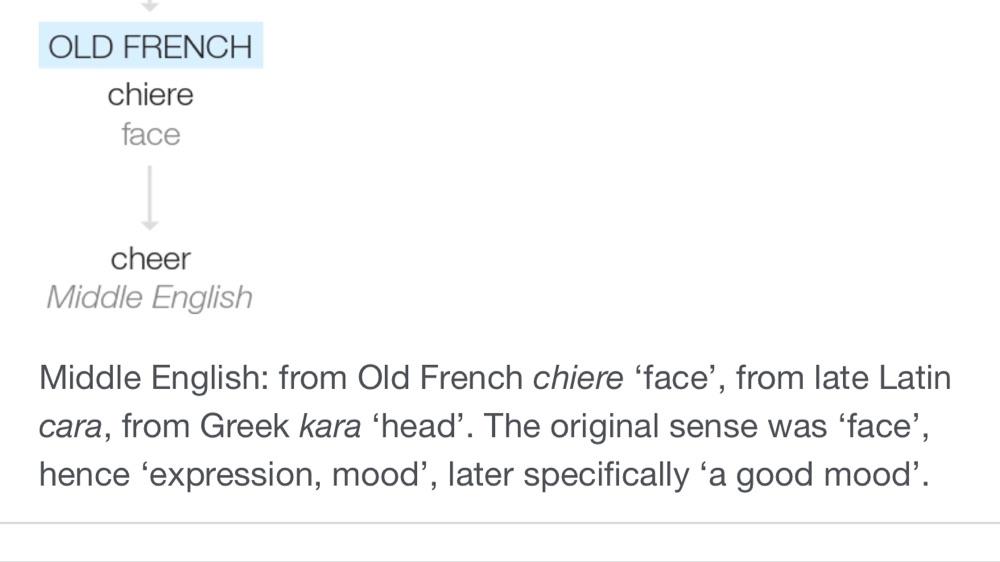

The Relationship Of “Cheer” And Face

This trajectory of cheerfulness through the self is linked to the history of the word “cheer” itself. “Cheer” comes from an Old French word that means, simply, “face”. The term comes into English and spreads through medieval culture in the 14th century. In Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (1387-1400), for example, people are depicted as having a “piteous cheer” or a “sober cheer”. “Cheer” is an expression, but also a body part. It lies at the intersection of our emotions and physiognomy.

24

134 reads

From Face To Expression, To Mood, To Emotional Quality

In the 16th century, the Protestant Reformation sparked intense debate over the meaning of spiritual community. At the same moment, when the Bible begins to be widely translated into vernacular languages, the simple noun “cheer” expands to encompass the adjective “cheerful”and, eventually, around 1530, includes the more abstract idea of “cheerful-ness”. which turns the local expression of the face into an abstract noun, something that can circulate as an emotional quality of the self.

23

126 reads

God Loves The Cheerful Giver (ἱλαρὸν γὰρ δότην ἀγαπᾷ ὁ Θεός)

In the Geneva Bible (1560), from Saint Paul’s “Second Letter to the Corinthians” we learn that to participate in the Christian community you must practise caritas , or love. “As every man wisheth in his heart,” says Paul, “so let him give; not grudgingly, or of necessity, for God loveth a cheerful giver.” God loveth a cheerful giver. These words resonated widely across the early modern world, linking cheer – and the face – to the practice of caritas, a social and religious activity.

23

110 reads

Do You Have A Cheerful Self If You Have A Cheerless Face?

Commentators on the Bible struggled to grasp the meaning of Saint Paul’s famous phrase. Erasmus of Rotterdam, the greatest intellectual of the day, linked the cheerful body to community, saying: ‘let thy thankful gift be increased and doubled with a merry look and cheerfulness.’ Giving is good. But giving cheerfully is even better, and your intentions may be seen through your ‘merry look’. Conversely, if you are not cheerful (with no merry look), you may not be a true Christian.

24

96 reads

Cheerfulness, True Faith And True Face

The suspicion that to be cheerless maybe meant to be unchristian was held by John Calvin, the great Protestant reformer. He suggested that stingy or reluctant participation in the charitable Christian community is the mark of Catholics, whom he saw as decadent and fearful of papal authority, whereas good Christians give cheerfully, with a glad visage. A bit later, the poet and preacher John Donne extended this idea, noting in a sermon that God gives his holy word to us, “not in a sour, and sullen, and angry, and unacceptable way, but cheerfully”.

24

82 reads

Cheerfulness (Re)Locates Us Socially And (Re)Links Us Communally

Modern readers might be struck in these early accounts by the extent to which cheerfulness is much more than the superficial performance of the upbeat colleague or the annoying salesman. A social quality, it shapes and defines a particular moral community. It emerges between people, binding them together. No wonder doctors sought to generate cheerfulness through chemical means.

24

89 reads

Cheerfulness Envelops

During the European Enlightenment, as the great religious debates of the early modern period begin to wane in Europe, the theological dimension of cheerfulness falls away. Yet its essential social dimension remains, as the characteristic of enlightened gatherings. The 18th-century Scottish philosopher David Hume notes that cheerfulness is a force that is larger than the individual. The individual doesn’t perform cheer, as Calvin had suggested; instead, it envelops him.

23

86 reads

Cheerfulness Sets Alight

Anyone who has ever passed an evening with “serious melancholy people”, Hume points out, can surely acknowledge that, when a good-humoured or gay person enters the room, “cheerfulness carries great merit with it, and naturally conciliates the good will of mankind … others enter into the same humour, and catch the sentiment, by a contagion or natural sympathy.” Cheerfulness is now a “contagion”. Elsewhere, Hume uses the metaphor of the flame to describe how cheerfulness might set a company alight.

25

77 reads

Cheerfulness Informs A Well-Lived Life

If cheerfulness is healthy and social, even morally upright, we can understand why the philosopher and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson understands it as a kind of power. Cheerfulness can condition our mood, but it also inflects our social being. It is essential to a healthy society. Whoever can control and harness it will possess a rare resource for shaping her emotional life and those of her fellows. For Emerson, the first great moral philosopher of the Americas, cheerfulness informs a well-lived life.

25

75 reads

“Without Cheerfulness No Man Can Be A Poet”

In his essay “Shakespeare, or the Poet”, Emerson asserts that poetic genius requires two things. First, the ability of the poet to see natural phenomena as moral phenomena – that is, to turn things in the world into metaphors of our inner lives. The poet turns things into signs that convey “a certain mute commentary on human life”. No less important is a second trait: the poet’s “cheerfulness, without which no man can be a poet – for beauty is his aim.” The poet’s cheerfulness involves his ability to see the beauty of the world, to see things “for the lovely light that sparkles from them”.

24

67 reads

Cheerfulness: Vision And Creativity

Emerson’s celebration of the cheerful sensibility brings the social vision of the moralist together with the creativity of the poet. He suggests not only that cheerfulness links people together in communities, but that he who controls cheerfulness can remake the world. Cheerfulness is a psychological and emotional force, originating in vision and sensibility.

25

71 reads

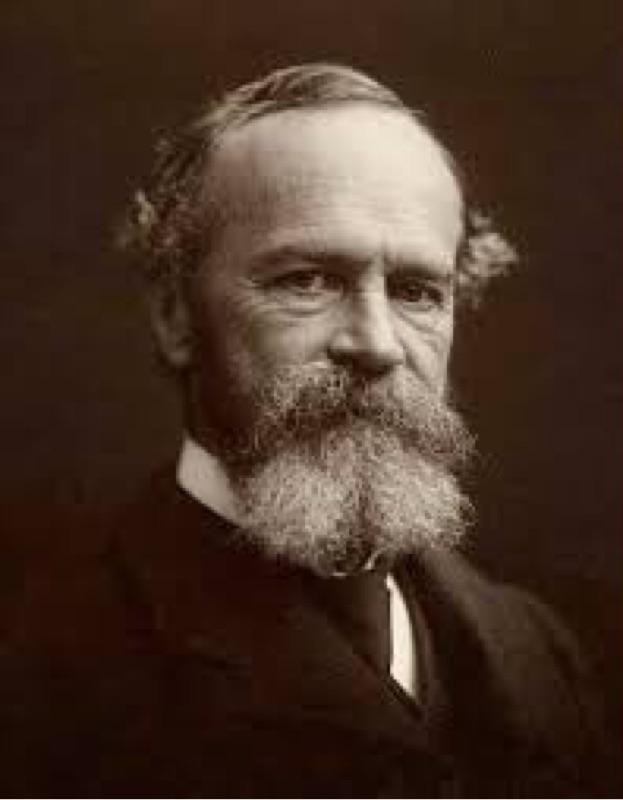

Cheerfulness: Happiness And Money

The turn of the 20th century saw a proliferation of what the philosopher William James called “mind-cure” movements – that is, approaches to living that assumed the influence of mental states on everyday productivity and social interaction. These movements swept cheerfulness along with them. The turn of the century “inspirational” writer Orison Swett Marden, who founded SUCCESS magazine, placed cheerfulness at the centre of his thought. Being upbeat, he claimed in his many titles, has advantages that are both personal and professional. It will make you happy – and it will make you money.

24

65 reads

Cheerfulness: A Bright Face And A Cheery Word

About the same time as Marden, the Boy Scouts of America published its first handbook, combining advice about such practical skills as how to build a fire in the woods, with moral encouragement toward a better life. The development of the self is governed by a “Scout Law”, consisting of 12 virtues. The 8th of these is cheerfulness. Here is how the Scouts define it:

“Another scout virtue is cheerfulness. As the scout law intimates, he must never go about with a sulky air. He must always be bright and smiling… A bright face and a cheery word spread like sunshine from one to another.”

24

57 reads

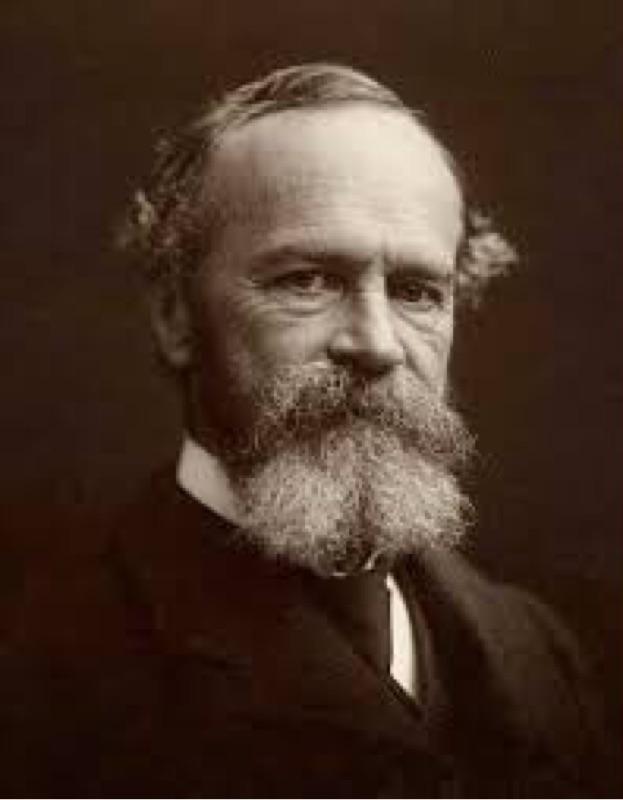

Actions seem to follow feeling, but really actions and feeling go together; and by regulating the action, which is under the more direct control of the will, we can indirectly regulate the feeling, which is not. Thus the sovereign voluntary path to cheerfulness, if our cheerfulness be lost, is to sit up cheerfully, to look round cheerfully, and to act and speak as if cheerfulness were already there.

WILLIAM JAMES

22

74 reads

Actions seem to follow feeling, but really actions and feeling go together; and by regulating the action, which is under the more direct control of the will, we can indirectly regulate the feeling, which is not. Thus the sovereign voluntary path to cheerfulness, if our cheerfulness be lost, is to sit up cheerfully, to look round cheerfully, and to act and speak as if cheerfulness were already there.

WILLIAM JAMES

24

76 reads

IDEAS CURATED BY

CURATOR'S NOTE

A cheery mood, we might think, is a terribly self-absorbed response to serious times. But history tells us otherwise.

“

Xarikleia 's ideas are part of this journey:

Learn more about problemsolving with this collection

Effective note-taking techniques

Test-taking strategies

How to create a study schedule

Related collections

Similar ideas

3 ideas

8 ideas

Read & Learn

20x Faster

without

deepstash

with

deepstash

with

deepstash

Personalized microlearning

—

100+ Learning Journeys

—

Access to 200,000+ ideas

—

Access to the mobile app

—

Unlimited idea saving

—

—

Unlimited history

—

—

Unlimited listening to ideas

—

—

Downloading & offline access

—

—

Supercharge your mind with one idea per day

Enter your email and spend 1 minute every day to learn something new.

I agree to receive email updates