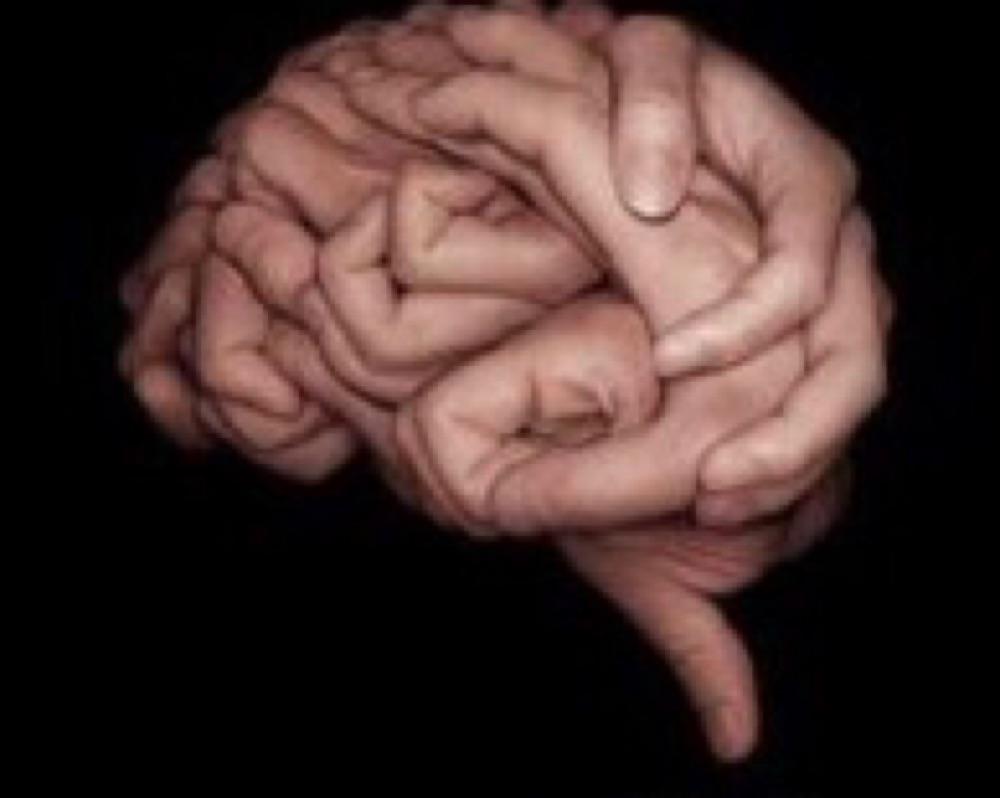

Can Collective Intelligence Be the Reason Why Human Brains Are Shrinking?

Curated from: interestingengineering.com

Ideas, facts & insights covering these topics:

13 ideas

·2.46K reads

18

Explore the World's Best Ideas

Join today and uncover 100+ curated journeys from 50+ topics. Unlock access to our mobile app with extensive features.

Smaller Brain = Less Intelligence?

The large size of the human brain is what makes us (arguably) the most intelligent creatures on Earth, but new research surprisingly reveals our brains may have been slowly shrinking from about 3,000 years ago. Are we getting less smart? Scientists aren’t ready to declare that yet, but have found a possible answer for the brain size mystery by studying ants and the use of collective intelligence in their social organizations.

28

419 reads

The Size Of Our Brain Through History

Researchers have found that for much of human evolutionary history our brains kept growing. In fact, if you count from our last shared ancestors with chimpanzees six million years ago, the human brain size almost quadrupled. This happened thanks in part to the improving diet and nutrition of early humans. Cro Magnons, the Homo sapiens that had the largest brains in history were alive from 20,000 to 30,000 years ago. But as the recent study from scientists at Dartmouth and Boston Universities points out, around 3,000 years ago, our brains began to diminish.

27

308 reads

Our Brain Was Always Growing And Growing. And Then It Stopped.

Previous research estimated that, over the past 20,000 years, the average volume of the human brain went from 1,500 cubic centimeters (cc) to 1,350 cc — shrinking by about 150 cc, or 10% (the size of a tennis ball, as commentators have pointed out.)

“Most people are aware that humans have unusually large brains—significantly larger than predicted from our body size. In our deep evolutionary history, human brain size dramatically increased,” said the new study’s other co-author James Traniello, of Boston University. “The reduction in human brain size was unexpected.”

28

245 reads

Why Did Our Brains Start Shrinking? Here’s Why They Did Not.

The big question of course is, “Why is our evolution going in reverse?” The interdisciplinary research team, which included a biological anthropologist, a behavioral ecologist and an evolutionary neurobiologist, write in the study that their dating techniques do not “support hypotheses concerning brain size reduction as a by-product of body size reduction, a result of a shift to an agricultural diet, or a consequence of self-domestication.”

26

236 reads

So, Why Did Our Brains Start Shrinking?

The scientists believe that the reason we don’t need the same size brains lies in the creation of our social systems, which favor distributed gathering and sharing of knowledge and information while offering advantages in “group-level decision-making.” Since brains use a lot of energy, being able to draw upon the knowledge gathered within a larger society would require less individual brain energy to be expended in order to store and process information. Thus a smaller brain would be able to do the job just as well.

26

216 reads

But What Was The Start Of It All?

Interestingly, the researchers also suggest that the advent of writing around 5,000 years ago likely had a pronounced effect on the “neural architectures” of individual human brains by increasing the power of group cognition. Decision-making by an increasingly interconnected group could have led to “adaptive group responses exceeding the cognitive accuracy and speed of individual decisions and had a fitness consequence.” This could have led to the human brain size decrease “as a consequence of metabolic cost savings.”

26

188 reads

And What Brought About That Idea?

Unexpectedly, the researchers arrived at their conclusions by studying ants. As the scientists write in their paper, “Humans live in social groups in which multiple brains contribute to the emergence of collective intelligence.” While understanding the historical forces affecting brain evolution in humans is a complex undertaking, with only the fossil record to use for evidence, the researchers looked at ant communities.

26

169 reads

Ant Sociality And Human Sociality

“The remarkable ecological diversity of ants and their species richness encompasses forms convergent in aspects of human sociality, including large group size, agrarian life histories, division of labor, and collective cognition,” explain the scientists in the study. The range of social systems in ant societies allowed them to test out hypotheses and come up with insights that provide a general look at how selective forces can affect brain size.

26

148 reads

Division Of Labour Affects Brain Size

The research team focused specifically on creating computational models that represent patterns of worker-ant brain size and energy use, looking at groups of Oecophylla weaver ants, Atta leafcutter ants, and the common garden ant Formica. What they found is that collective intelligence and division of labor had an effect on the variation in brain sizes. In a group with shareable knowledge and individual specialization in particular tasks, brains were likely to adapt for the sake of efficiency, consequently diminishing in size.

27

120 reads

Ants Are Not Humans, Of Course

“Ant and human societies are very different and have taken different routes in social evolution,” Traniello shared. “Nevertheless, ants also share with humans important aspects of social life such as group decision-making and division of labor, as well as the production of their own food (agriculture). These similarities can broadly inform us of the factors that may influence changes in human brain size.”

27

129 reads

In 1946, Dr. Caryl P. Haskins Wrote “Of Ants and Men”

A review of the book in The American Journal of Sociology read:

“After many years” observation of the behaviour of ants, the author has written a popular book attempting to show how ant societies function, how they solve many of the ‘social problems’ confronting man - war, reproduction, sustenance, pressure groups, security, democracy, and totalitarianism. In addition, one finds a tracing of the rise of the ants as a race, their diversification, their struggles for dominance, their tastes for odors, forms, and textures, their modes of ‘gossip’ and memories.”

26

121 reads

“Go To The Ant”

As the author of “Of Ants and Men” himself remarked in 1946, the question is how far can we compare these ant societies with our own without becoming hopelessly involved in a bog of anthropomorphism? In other words, he goes on to reflect, can we legitimately “go to the ant” without reading into our findings many things that really do not exist?

While this new research doesn’t have definitive answers, the new modeling is a fascinating step forward in getting closer to a fuller picture of our evolutionary transformation.

11

79 reads

IDEAS CURATED BY

CURATOR'S NOTE

The human brain shrank in size about 3,000 years ago. Scientists may have found an explanation by studying ants.

“

Xarikleia 's ideas are part of this journey:

Learn more about scienceandnature with this collection

How to build trust in a virtual environment

How to manage remote teams effectively

How to assess candidates remotely

Related collections

Similar ideas

Read & Learn

20x Faster

without

deepstash

with

deepstash

with

deepstash

Personalized microlearning

—

100+ Learning Journeys

—

Access to 200,000+ ideas

—

Access to the mobile app

—

Unlimited idea saving

—

—

Unlimited history

—

—

Unlimited listening to ideas

—

—

Downloading & offline access

—

—

Supercharge your mind with one idea per day

Enter your email and spend 1 minute every day to learn something new.

I agree to receive email updates