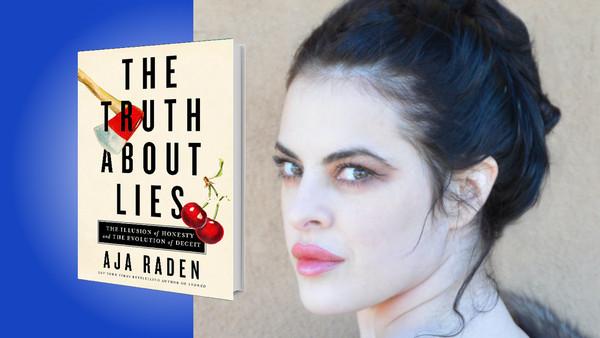

The Truth About Lies: The Illusion of Honesty and the Evolution of Deceit

Curated from: nextbigideaclub.com

Ideas, facts & insights covering these topics:

21 ideas

·6.24K reads

41

2

Explore the World's Best Ideas

Join today and uncover 100+ curated journeys from 50+ topics. Unlock access to our mobile app with extensive features.

1. You’re a natural-born liar.

We all lie, all the time—including you. Human deception is no different from its animal equivalent of camouflage, spots, and stripes. Charm is our very own version of frilly fins and peacock feathers. Like a stick insect adapted to hide among twigs, the effort to deceive, from camouflage to creative bullshit, is an evolutionary arms race as old as organic life.

38

679 reads

Trickery is fundamental to interaction, and the instinct to misrepresent objective reality to suit our needs is fundamental to communication. In the evolution of deceit, language only came about quite recently, billions of years after more basic and more effective tools of the con. In fact, humans may have developed language specifically to manipulate each other in new and cleverer ways; it’s just the latest innovation in a billion-year-old chess game.

37

506 reads

As Rutgers Professor of Anthropology and Biological Sciences Robert Trivers put it, “Our most prized possession, language, not only strengthens our ability to lie, but greatly extends its range.” Consider that when you lie with your scent, your pattern, or your petals, you can only lie about what you are, here and now. But lie with words, and you can lie about anything, anyone, anywhere; you can rewrite facts past, present, and future. In other words, human speech allows deceptions to transcend space and time. Dishonesty is truly a feature, not a bug, of our nature.

40

410 reads

Jefferson Randolph Smith was a con man who set up the first telegraph office out of Skagway, Alaska. For the price of five dollars, settlers, frontiersmen, and prospectors could send a telegraph message to anyone in the United States. Unsurprisingly, there were lines around the building every day. It was great business—even though the first telegraph wires didn’t actually arrive in Alaska until two years later.

37

358 reads

In the absence of evidence, humans tend to believe that whatever we’re presented with is true—be it someone’s name, a random fact, a complex explanation, even something as obvious as the presence of a physical object we see Neurologists refer to this tendency as the “honesty bias,” and it’s how we know almost everything that we know. It’s because of your honesty bias that you don’t automatically wonder if a lamp is a hallucination that only you can see, or suspect that everyone you meet might be lying about their name. If we didn’t lean toward this neurological shortcut, we’d all go insane.

40

305 reads

It’s also the single adaptation that has allowed humans to develop speech, literacy, history, science, and civilization itself. You don’t have to discover, confirm, or even understand every fact or idea you learn, because you are biased to just accept them as true and keep climbing. This is the mechanism behind our species’ collective intelligence: To rapidly acquire another’s lifetime of experience or problem-solving for ourselves, all we need to do is ask—and then trust the answer.

38

269 reads

3. Lies take advantage of the way we perceive—and construct—reality.

Seeing may be believing, but it really shouldn’t be. Your brain doesn’t actually have the processing power to deal with all of the sensory data available at every second—so, like all gamblers, it cheats. As a result, we often end up seeing what we expect to see.

Take shell games; everybody falls for sleight of hand because it exploits several loopholes in perceptual cognition, the ways in which your brain processes and interprets input from your senses. In other words, if you have a normally functioning brain, you literally can’t not fall for it.

36

239 reads

Your visual cortex—the part of the brain that processes electrical signals from the retina and turns them into images in your mind—functions with a 0.1-second delay. So you can’t believe your eyes, because while your eyes may work, your brain is processing everything your eyes pick up about one-tenth of a second behind what’s happening.

36

223 reads

There are other exploitable neurological loopholes as well—for example, there’s the mirroring effect. Mirroring is when specialized cells in your brain called “mirror neurons” cause you to imitate the gesture, posture, or subtle movements of whomever you’re interacting with. Someone smiles, you smile back. Someone looks up suddenly, you look up too. You assume these are conscious choices, but they’re not—and it’s an incredibly effective way to make people look (or not look) at whatever you want.

36

210 reads

4. What matters is not if something is true, but if it is believed.

In 1898, four Denver reporters from different newspapers went to a bar, got really drunk, and made up a story. They all claimed in their separate papers to have met a team of four American engineers on their way to China. The engineers, they said, told them that they’d been hired to destroy the Great Wall at China’s request. Supposedly this was being done as a gesture of goodwill, and as an invitation to foreign trade.

36

213 reads

It was a multi-person hoax, and unfortunately, other newspapers picked up the story, and it went viral. Within weeks, a major east coast newspaper did an entire special Sunday spread about the fake destruction of the Great Wall, including elaborate illustrations and further exposition about the Chinese government’s historic plan to end their isolationist policy.

35

202 reads

Because this was a respected newspaper, the story quickly spread to Europe, then to Asia, and finally to China, where political tempers were already running high. In fact, this fiction allegedly contributed to the Boxer Rebellion, a destabilizing and violent disaster that hastened the decline of the Qing Dynasty.

35

198 reads

The point of this story is not that a single fake news story may have radically altered the course of 20th-century Chinese history—though it did—it’s that the Boxer Rebellion occurred just as it would have had the news been real. The cause may have been fictitious, but it had the same effect as its truthful parallel.

35

189 reads

5. Nothing is entirely real.

If a whole civilization believes certain objects have power or value, and everyone behaves accordingly, then for all intents and purposes, they do possess that value or power. It may be a lie, but a quality counterfeit object still works precisely the same way the real object would—for exactly as long as it is believed to be authentic. And if a thing only needs to be believed in to be effective, then that begs the question: Was there ever anything to value or authority other than belief in the first place?

36

185 reads

Why we lie and how we believe are so inextricably intertwined that there can be no faith without fraud, no truth without lies, no civilization without cons. Whether they’re the lies we tell each other, or the subtler and more complicated lies we tell ourselves, deceit and belief are two halves of one whole. One can’t exist without the other, and society can’t function without both.

37

202 reads

IDEAS CURATED BY

CURATOR'S NOTE

The Truth About Lies: The Illusion of Honesty and the Evolution of Deceit

“

Tom Joad's ideas are part of this journey:

Learn more about psychology with this collection

How to develop a healthy relationship with money

How to create a budget

The impact of emotions on financial decisions

Related collections

Similar ideas

4 ideas

3 ideas

Do You Notice the Signs When Someone Is Lying?

verywellmind.com

Read & Learn

20x Faster

without

deepstash

with

deepstash

with

deepstash

Personalized microlearning

—

100+ Learning Journeys

—

Access to 200,000+ ideas

—

Access to the mobile app

—

Unlimited idea saving

—

—

Unlimited history

—

—

Unlimited listening to ideas

—

—

Downloading & offline access

—

—

Supercharge your mind with one idea per day

Enter your email and spend 1 minute every day to learn something new.

I agree to receive email updates