The Complete Guide to Motivation | Scott H Young

Curated from: scotthyoung.com

Ideas, facts & insights covering these topics:

14 ideas

·34.4K reads

67

3

Explore the World's Best Ideas

Join today and uncover 100+ curated journeys from 50+ topics. Unlock access to our mobile app with extensive features.

The first views on motivation

- At first, psychologist William James thought that only the initial act was conscious, thereafter behaviour was a spontaneous cascade of habits. He suggested we struggle with motivation when there are competing ideas.

- Sigmund Freud theorised that we are largely unconscious of what drives our behaviour.

1.17K

10.3K reads

Mathematics of motivation

When Ivan Pavlov and his dogs led to the discovery of learned behaviour through repeated exposure, and Edward Thorndike discovered the Law of Effect that stated that rewarded behaviours tended to increase, many psychologists were impelled to separate psychology from armchair introspection and formulated their theories as mathematical formulas.

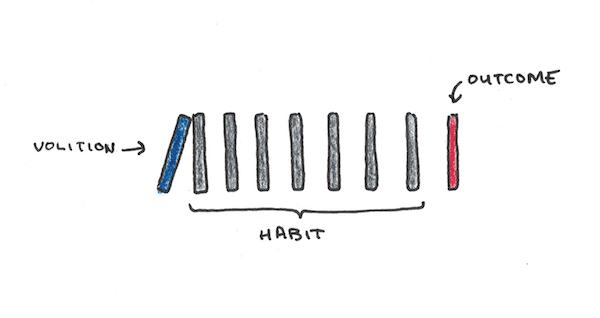

- The Drive x Habit Theory. Clark Hull's formula was sEr = D x sHr, which states that excitatory tendency (E) is the result of the drive (D) combined with the habit (H). The drive is nonspecific, such as hunger or thirst. The habit, however, depends on the stimulus (s) and response (r). But the theory turned out to be wrong and even opposite in many cases.

- Expectation x Value Theory. Drawing on ideas in economics and game theory, Edward Tolman and Kurt Lewis formulated an alternative account by evaluating motivation based on expectations. Tolman expressed the ideas as the mathematical formula: Subjective Expected Utility = Probability1 * Utility1 + P2U2 + P3U3 + … where subjective expected utility of an action equalled the motivation to act. But, if you expect a reward, why act and not simply passively wait for the expected reward?

928

3K reads

Motivation as change

Donald Hebb realised that existing theories were too focused on reacting to the immediate environment. Thoughts, ideas and goals could be just as strong for triggering action as sights and sounds.

Together with John Atkinson, they noted that the study of motivation had undergone a "paradigm shift", where motivation couldn't be seen as how actions get started, but how the organism decides to change its behaviour from one thing to another.

889

2.75K reads

Reinforcement learning

Thorndike’s Law of Effect led B.F. Skinner to the study of instrumental conditioning, where behaviour could be manipulated by applying rewards and punishments.

To describe this paradigm, some terminology is useful since they are often confused in popular discussions:

- Positive reinforcement. Rewarding a behaviour.

- Positive punishment. Something bad decreases a behaviour, such as shocking an animal that gives an incorrect response.

- Negative reinforcement. Removing something bad to increase behaviour.

- Negative punishment. Removing something good to decrease behaviour.

914

2.53K reads

The neuroscience of motivation

Neuroscience offers clues on how motivation works within the brain.

- Taking action. The motor loop in the brain enables one-action-at-a-time control. (We can't sit down and stand up at the same time.)

- The dopamine network explains which action we will pick. It signals to the brain which action will bring a reward. It uses that anticipation to guide our thoughts and behaviour.

- Addiction is a motivational disorder. Some drugs act directly upon the motivational circuitry of the brain, and cause the motivation to do something to far exceeds its value.

- Fear and anxiety compel us to do the opposite of motivation. The amygdala is a "threat detection centre" and forces us to suppress and avoid actions when we are anxious.

1K

2.34K reads

The self-determination theory

This theory is not focused on how human motivation can be controlled and manipulated from without, but how it is functionally designed and experienced from within.

Intrinsic motivation is when we are more motivated to pursue actions when it emanates from the self. Extrinsic incentives and rewards have the potential to decrease intrinsic motivation. However, the form of reward matters greatly. If the reward is not directly related to the completion of the activity, it does not have a negative effect.

894

1.98K reads

The six levels of motivation

- A-motivation. An utter lack of motivation to act.

- External regulation. When you're motivated to act based on external rewards and punishments.

- Introjection. Your motives to act come primarily from guilt/shame. Even when contingencies are removed, you may perform it, such as going to a medical school because your parent's desire it.

- Identification. When you agree to the behaviour and identify personally with the reasons.

- Integration. When identification becomes a part of your identity.

- Intrinsic motivation. When you spontaneously engage in the activity for its inherent value.

The experience of actions starting from oneself is a matter of degree. Some actions are controlled, while others feel spontaneous. Most are somewhere in-between.

987

1.9K reads

Motivation and psychological needs

People have three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Our internal motivations often depend on how these needs are met.

Goals that satisfy these needs tend to be more motivating, while goals that don't may cause harm. The underlying reasons for a goal may matter more.

905

1.73K reads

Modelling motivation: rationality, signaling and bias

- Rational choice theory suggests that human behaviour is underpinned by the motivations of each individual. More specifically, this theory models human beings as utility-maximizers, according to a set of preferences. If you give people a set of actions to choose from, they will do whatever improves their utility the most.

- Signalling is the idea of taking an action because of what it communicates about you. For example, we care more for credentials in education than learning.

- The prospect theory states that we are reliably irrational in our decision-making. One possible bias is loss aversion that argues that we'll work harder to avoid losses than to get equivalent gains.

879

1.35K reads

Curiosity and boredom are a form of motivation for learning

- Information-gap theory of curiosity. This theory argues that the intensity of curiosity is controlled by the gap between what you know and what you want to know.

- Friston and free energy of human neuroscience places the search for information as the central organizing principle of the entire brain. It argues that we are motivated to reduce uncertainty.

- Learning progress is a simple model that states that we are motivated to learn wherever we experience the most gain. When we focus on learnable situations we haven't yet grasped, we can unlock new opportunities.

- Boredom signals that you're not engaged with the material. It may be a sign that you need to adjust your attention rather than change tasks.

907

1.3K reads

Procrastination: why we struggle to start

Procrastination is delaying an intended course of action despite expecting negative consequences for the delay.

Possible causes for procrastination:

- Task unpleasantness. Boring, frustrating and aversive tasks.

- Self-efficacy. Believing in your ability to do a task.

- Task delay when rewards and punishments are more distant.

- Impulsiveness. You are easily distractable and less able to resist it.

- Organization. Being more organized is associated with less procrastination.

- Achievement motivation. The higher you value achievement, the less you will procrastinate.

Learned industriousness claims that when you are rewarded for expending higher effort, the experience of effortful activity itself is reinforced, leading to a willingness to work harder for bigger payoffs.

954

1.42K reads

Goals: how intentions impact results

- Goals direct your attention to relevant information and tasks.

- Goals give you the energy to act on various physical and cognitive tasks.

- Goals increase your persistence. It enables you to endure for longer before giving up.

- Goals encourage you to find better strategies. Having a better method can lead to better performance.

- Harder goals that are accepted by the participant will lead to better performance than easier goals.

- Focusing on a specific target will produce better results than merely doing your best. However, the goal should not be set too high, as it can have the opposite effect.

- Goals can be made more effective when they are connected to implementation intentions. "I intend to write every morning at 7 am."

937

1.26K reads

Motivation and identity: what you believe about yourself

- Self-efficacy. When we feel we can do something. The social-cognitive theory is the idea that we learn by witnessing others, not only by trying things ourselves. Yet, sometimes we don't (or choose not to) learn from the example of others. If you believe you cannot perform well or master a particular skill, you're unlikely to do so.

- Group impact motivation. When you are attending a school which out-performs you academically, you may be highly motivated. But placed in a superior school where everyone is equally talented, your self-conception and motivation may drop.

- Self-comparison. If you are good at more than one thing, you may be more motivated to focus on what you are better at. For example, preferring maths over English, if your self-concept is that you are a "math" person.

895

1.19K reads

Improving your life with motivation

While motivation is a huge topic, and the science on it is not in agreement, there are many takeaways we can use to understand how motivation operates and use it to improve our lives.

- Rewards and punishments are at the centre of motivation. For example, we may not be able to consciously link our love of sports to early childhood experiences.

- Consciously setting our intentions greatly impacts our performance. When we reframe a situation, we can be more motivated to do it.

- There are many positive feedback loops. Set hard goals and commit to them, and our performance increases. If you feel you can't do anything, your motivation diminishes.

- Motivational struggles are caused by competing forces. We might find it harder to read books in our spare time when we have easy access to Netflix.

- Many sources of motivation may be hidden from view. Our motivation is often hidden from us. Sometimes it is simply because the hardware that runs our motivation is not expressible. In other cases, motivations may be subtle and complex.

912

1.29K reads

IDEAS CURATED BY

Zara Michaels's ideas are part of this journey:

Learn more about personaldevelopment with this collection

How to create a positive work environment

Techniques for cultivating gratitude and mindfulness at work

How to find purpose in your work

Related collections

Similar ideas

9 ideas

The Complete Guide to Self-Control | Scott H Young

scotthyoung.com

4 ideas

3 ideas

Should You Even Try to Motivate Yourself? | Scott H Young

scotthyoung.com

Read & Learn

20x Faster

without

deepstash

with

deepstash

with

deepstash

Personalized microlearning

—

100+ Learning Journeys

—

Access to 200,000+ ideas

—

Access to the mobile app

—

Unlimited idea saving

—

—

Unlimited history

—

—

Unlimited listening to ideas

—

—

Downloading & offline access

—

—

Supercharge your mind with one idea per day

Enter your email and spend 1 minute every day to learn something new.

I agree to receive email updates