Xarikleia 's Key Ideas from On Anger

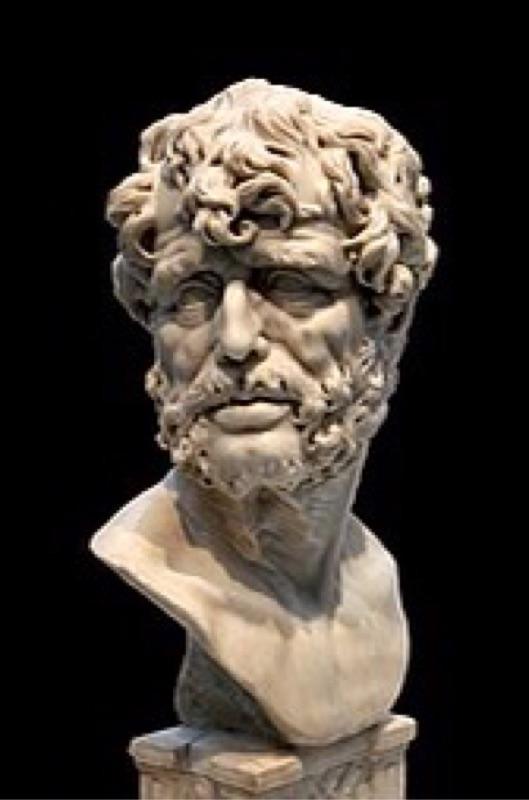

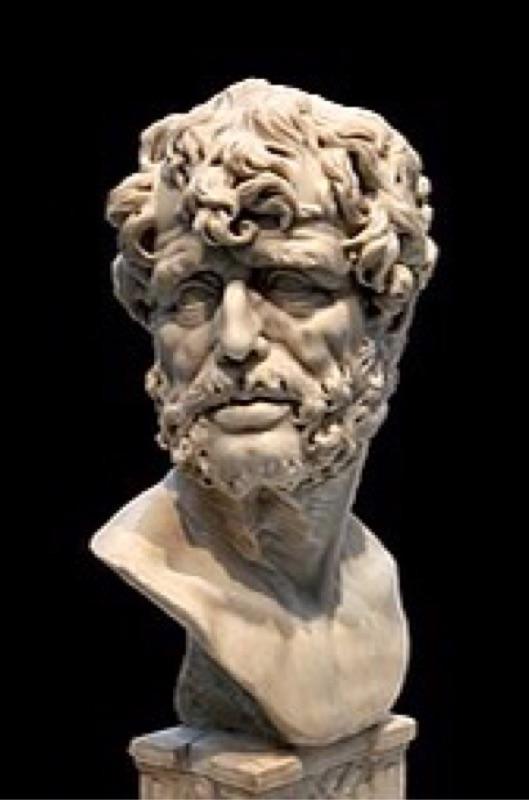

by Seneca

Ideas, facts & insights covering these topics:

26 ideas

·10.7K reads

48

3

Explore the World's Best Ideas

Join today and uncover 100+ curated journeys from 50+ topics. Unlock access to our mobile app with extensive features.

It appears to me that you are right in feeling especial fear of [the passion of anger], which is above all others hideous and wild: for the other [passions] have some alloy of peace and quiet, but this consists wholly in action and the impulse of grief, raging with an utterly inhuman lust for arms, blood and tortures, careless of itself provided it hurts another, rushing upon the very point of the sword, and greedy for revenge even when it drags the avenger to ruin with itself.

SENECA

100

2.1K reads

Some of the wisest of men have […] called anger a short madness: for it is equally devoid of self control, regardless of decorum, forgetful of kinship, obstinately engrossed in whatever it begins to do, deaf to reason and advice, excited by trifling causes, awkward at perceiving what is true and just, and very like a falling rock which breaks itself to pieces upon the very thing which it crushes.

SENECA

103

1.33K reads

There is no animal so hateful and venomous by nature that it does not, when seized by anger, show additional fierceness. I know well that the other passions, can hardly be concealed, and that lust, fear, and boldness give signs of their presence and may be discovered beforehand, for there is no one of the stronger passions that does not affect the countenance: what then is the difference between them and anger? Why, that the other passions are visible, but that this is conspicuous.

SENECA

92

959 reads

Aristotle’s definition [of anger] differs little from mine: for he declares anger to be a desire to repay suffering. It would be a long task to examine the differences between his definition and mine: it may be urged against both of them that wild beasts become angry without being excited by injury, and without any idea of punishing others or requiting them with pain: for, even though they do these things, these are not what they aim at doing.

SENECA

88

733 reads

We must admit, however, that neither wild beasts nor any other creature except man is subject to anger: for, whilst anger is the foe of reason, it nevertheless does not arise in any place where reason cannot dwell. Wild beasts have impulses, fury, cruelty, combativeness: they have not anger any more than they have luxury: yet they indulge in some pleasures with less self-control than human beings.

SENECA

87

629 reads

When [the poet] speaks of beasts being angry he means that they are excited, roused up: for indeed they know no more how to be angry than they know how to pardon. Dumb creatures have not human feelings, but have certain impulses which resemble them. […] Their impulses and outbreaks are violent, [but] they do not feel fear, anxieties, grief, or anger, but some semblances of these feelings: wherefore they quickly drop them and adopt the converse of them: they graze after showing the most vehement rage and terror, and after frantic bellowing and plunging they straightway sink into quiet sleep.

SENECA

86

459 reads

The difference between [anger] and irascibility is evident: it is the same as that between a drunken man and a drunkard; between a frightened man and a coward. It is possible for an angry man not to be irascible; an irascible man may sometimes not be angry.

SENECA

90

508 reads

[There] are some sorts of anger which go no further than noise, while some are as lasting as they are common: some are fierce in deed, but inclined to be sparing of words: some expend themselves in bitter words and curses: some do not go beyond complaining and turning one’s back: some are great, deep- seated, and brood within a man: there are a thousand other forms of a multiform evil.

SENECA

89

403 reads

Whether [anger is] according to nature will become evident if we consider man’s nature […] Mankind is born for mutual assistance, anger for mutual ruin: the former loves society, the latter estrangement. The one loves to do good, the other to do harm; the one to help even strangers, the other to attack even its dearest friends. The one is ready even to sacrifice itself for the good of others, the other to plunge into peril provided it drags others with it.

SENECA

89

347 reads

“What, then? Is not correction sometimes necessary?” Of course it is; but with discretion, not with anger; for it does not injure, but heals under the guise of injury. We char crooked spearshafts to straighten them, and force them by driving in wedges, not in order to break them, but to take the bends out of them.

SENECA

88

346 reads

May it not be that, although anger be not natural, it may be right to adopt it, because it often proves useful? It rouses the spirit and excites it; and courage does nothing grand in war without it, unless its flame be supplied from this source […] Some therefore consider it to be best to control anger, not to banish it utterly, but to cut off its extravagances, and force it to keep within useful bounds, so as to retain that part of it without which action will become languid and all strength and activity of mind will die away.

SENECA

87

296 reads

In the first place, it is easier to banish dangerous passions than to rule them; it is easier not to admit them than to keep them in order when admitted; for when they have established themselves in possession of the mind they are more powerful than the lawful ruler, and will in no wise permit themselves to be weakened or abridged. In the next place, Reason herself, who holds the reins, is only strong while she remains apart from the passions; if she mixes and befouls herself with them she becomes no longer able to restrain those whom she might once have cleared out of her path.

SENECA

88

277 reads

There are certain things whose beginnings lie in our own power, but which, when developed, drag us along by their own force and leave us no retreat. Those who have flung themselves over a precipice have no control over their movements, nor can they stop or slacken their pace when once started […] So, also, the mind, when it has abandoned itself to anger, love, or any other passion, is unable to check itself: its own weight and the downward tendency of vices must needs carry the man off and hurl him into the lowest depth.

SENECA

87

274 reads

The mind does not stand apart and view its passions from without, so as not to permit them to advance further than they ought, but it is itself changed into a passion, and is therefore unable to check what once was useful and wholesome strength, now that it has become degenerate and misapplied: for passion and reason, as I said before, have not distinct and separate provinces, but consist of the changes of the mind itself for better or for worse.

SENECA

69

185 reads

“But some angry men remain consistent and control themselves.” When do they do so? It is when their anger is disappearing and leaving them of its own accord, not when it was red-hot, for then it was more powerful than they; […] it is when one passion overpowers another, and either fear or greed gets the upper hand for a while. On such occasions, it is not thanks to reason that anger is stilled, but owing to an untrustworthy and fleeting truce between the passions.

SENECA

69

175 reads

[A]nger has nothing useful in itself, and does not rouse up the mind to warlike deeds: for a virtue, being self-sufficient, never needs the assistance of a vice: whenever it needs an impetuous effort, it does not become angry, but rises to the occasion, and excites or soothes itself as far as it deems requisite.

SENECA

69

175 reads

“Anger,” says Aristotle, “is necessary, nor can any fight be won without it, unless it fills the mind, and kindles up the spirit. It must, however, be made use of, not as a general, but as a soldier.”

Now this is untrue; for if it listens to reason and follows whither reason leads, it is no longer anger, whose characteristic is obstinacy: if, again, it is disobedient and will not be quiet when ordered, but is carried away by its own willful and headstrong spirit, it is then as useless an aid to the mind as a soldier who disregards the sounding of the retreat would be to a general.

SENECA

69

164 reads

If, therefore, anger allows limits to be imposed upon it, it must be called by some other name, and ceases to be anger, which I understand to be unbridled and unmanageable: and if it does not allow limits to be imposed upon it, it is harmful and not to be counted among aids: wherefore either anger is not anger, or it is useless […]

the passions cannot obey any more than they can command.

SENECA

69

159 reads

For this cause reason will never call to its aid blind and fierce impulses, over whom she herself possesses no authority, and which she never can restrain save by setting against them similar and equally powerful passions, as for example, fear against anger, anger against sloth, greed against timidity. May virtue never come to such a pass, that reason should fly for aid to vices!

SENECA

69

166 reads

Moreover, of what use is anger, when the same end can be arrived at by reason? Do you suppose that a hunter is angry with the beasts he kills? Yet he meets them when they attack him, and follows them when they flee from him, all of which is managed by reason without anger.

SENECA

58

149 reads

Anger […] is not useful even in wars or battles: for it is prone to rashness, and while trying to bring others into danger, does not guard itself against danger.

The most trustworthy virtue is that which long and carefully considers itself, controls itself, and slowly and deliberately brings itself to the front.

SENECA

59

145 reads

No passion is more eager for revenge than anger, and for that very reason it is unapt to obtain it: being over hasty and frantic, like almost all desires, it hinders itself in the attainment of its own object, and therefore has never been useful either in peace or war: for it makes peace like war, and when in arms forgets that Mars belongs to neither side, and falls into the power of the enemy, because it is not in its own.

SENECA

58

137 reads

Vices ought not to be received into common use because on some occasions they have effected somewhat: for so also fevers are good for certain kinds of ill-health, but nevertheless it is better to be altogether free from them: it is a hateful mode of cure to owe one’s health to disease. Similarly, although anger, like poison, or falling headlong, or being shipwrecked, may have unexpectedly done good, yet it ought not on that account to be classed as wholesome, for poisons have often proved good for the health.

SENECA

58

140 reads

Qualities which we ought to possess become better and more desirable the more extensive they are: if justice is a good thing, no one will say that it would be better if any part were subtracted from it; if bravery is a good thing, no one would wish it to be in any way curtailed: consequently the greater anger is, the better it is, for whoever objected to a good thing being increased? But it is not expedient that anger should be increased: therefore it is not expedient that it should exist at all, for that which grows bad by increase cannot be a good thing.

SENECA

58

137 reads

No man becomes braver through anger, except one who without anger would not have been brave at all: anger does not therefore come to assist courage, but to take its place.

SENECA

60

167 reads

Nothing becomes one who inflicts punishment less than anger, because the punishment has all the more power to work reformation if the sentence be pronounced with deliberate judgment. This is why Socrates said to the slave, “I would strike you, were I not angry.” He put off the correction of the slave to a calmer season; at the moment, he corrected himself. Who can boast that he has his passions under control, when Socrates did not dare to trust himself to his anger?

SENECA

60

158 reads

IDEAS CURATED BY

CURATOR'S NOTE

“No plague has cost the human race more dear.” - Seneca

“

Xarikleia 's ideas are part of this journey:

Learn more about books with this collection

How to build confidence

How to connect with people on a deeper level

How to create a positive first impression

Related collections

Different Perspectives Curated by Others from On Anger

Curious about different takes? Check out our book page to explore multiple unique summaries written by Deepstash curators:

Discover Key Ideas from Books on Similar Topics

5 ideas

How to Keep Your Cool

Seneca

1 idea

The Handbook (The Encheiridion)

Epictetus

5 ideas

How to Die

Seneca

Read & Learn

20x Faster

without

deepstash

with

deepstash

with

deepstash

Personalized microlearning

—

100+ Learning Journeys

—

Access to 200,000+ ideas

—

Access to the mobile app

—

Unlimited idea saving

—

—

Unlimited history

—

—

Unlimited listening to ideas

—

—

Downloading & offline access

—

—

Supercharge your mind with one idea per day

Enter your email and spend 1 minute every day to learn something new.

I agree to receive email updates