Explore the World's Best Ideas

Join today and uncover 100+ curated journeys from 50+ topics. Unlock access to our mobile app with extensive features.

Introduction

Nobody is immune to cognitive errors, unconscious thinking habits that lead to false conclusions or poor decisions. Mere mortals are prone to an array of common thinking errors and will consistently overestimate their chances of success, prefer stories to facts, confuse the message with the messenger, become overwhelmed by choices and ignore alternative options. Knowing these errors won’t help you avoid them completely, but it will help you make better decisions – or at least teach you where you slipped.

213

2.49K reads

It’s Normal as a Human to Have Errors

Human beings are prone to cognitive errors, or barriers to clear, logical thinking. Everyone experiences flawed patterns in the process of reasoning. In fact, many of these common mistakes have a history that goes back centuries. Even experts fall prey to such glitches, which might explain why supposedly savvy financiers hold investments for too long. Identifying “systematic cognitive errors” will help you avoid them. Becoming familiar with these pitfalls will improve your ability to make astute decisions. Below are selections of cognitive errors to avoid their consequences:

199

1.64K reads

1. Survivorship Bias

Tales of authors self-publishing bestsellers or college athletes signing with the major leagues for millions are so inspiring that people tend to overestimate their own chances of duplicating such career trajectories. This bias makes most folks focus on the few stars who soar, not the millions of ordinary humans who falter. This tendency is quite pernicious among investors and entrepreneurs. Dose yourself in reality and avoid this pitfall “by frequently visiting the graves of once-promising projects, investments and careers.”

206

1.5K reads

2. Swimmer’s Body Illusion

You admire the slim physique of a professional swimmer, so you head for the local pool, hoping that you, too, can attain such a sleek body. You’ve fallen prey to the swimmer’s body illusion that causes you to confuse “selection factors” with results. Does Michael Phelps have a perfect swimmer’s body because he trains extensively, or is he the world’s top competitive swimmer because he was born with a lean, muscular build? Does Harvard mold the world’s best and brightest, or do the smartest kids choose Harvard? These chicken-and-egg question arise between selection criteria and results.

211

1.35K reads

3. Sunk Cost Fallacy

The old saying about ‘throwing good money after bad’ expresses the heart of this fallacy: the tendency to persevere with a project once you’ve invested “time, money, energy or love” in it, even after the thrill or profit potential is gone. This is why marketers stick with campaigns that fail to show results, why investors hold stocks that keep losing value, and why Britain and France sunk billions into the Concorde aircraft when it was clearly a dud. When deciding how long you want to continue a project, exclude incurred costs from your evaluation and keep the good money

205

1.18K reads

4. Confirmation Bias

People tend to discount information that conflicts with their beliefs. Executives emphasize evidence that their strategies work and rationalize away contrary indicators. Yet exceptions aren’t just outliers; they often disprove fixed ideas. If you’re an optimist, you’ll corroborate your positive viewpoint at every turn; if you’re a pessimist, you’ll find many reasons to see a situation negatively. People focus on feedback that fits their worldview. Protect yourself from this bias by emulating Charles Darwin, who researched every item that contradicted his previous findings.

206

1K reads

“Nature doesn’t seem to mind if our decisions are perfect or not, as long as we can maneuver ourselves through life – and as long as we are ready to be rational when it comes to the crunch.”

ROLF DOBELLI

198

1.2K reads

5. Story Bias

People find information easier to understand in story form. Facts are dry and difficult to remember; tales are engaging. People more easily find meaning in historical events, economic policy and scientific breakthroughs through stories. Relying on narratives to explain the world leads to story bias, which, unfortunately, distorts reality.

The “fundamental attribution error” is a related misconception. People tend to give credit or blame to a person rather than a set of circumstances. Thus, CEOs receive undue credit for a firm’s profits, or crowds cheer coaches when teams win.

206

874 reads

5. Story Bias (contd)

Say that a car was driving across a bridge when the structure collapsed. A journalist covers the story by finding out about the driver, detailing his backstory and interviewing him about the experience. This puts a face on the incident, something readers want and need. But it ignores other pertinent questions: What caused the bridge to fall? Are other bridges at risk? Have authorities looked into the bridge’s compliance with engineering regulations? To dispel the false sense of knowledge that news stories bestow, learn to read between the lines and ask the unspoken questions.

201

745 reads

6. Overconfidence Effect

Most folks believe that they are intelligent and can make accurate predictions based on their knowledge. In most cases, they can’t. People, especially specialists and experts, overestimate how much they know. Economists are notoriously bad at predicting long-term stock market performance, for example. In spite of statistics to the contrary, restaurateurs believe their eateries will outperform the average, though most dining establishments close within three years. Counter this cognitive error by becoming a pessimist, at least in terms of plans that require your time or your hard-earned cash.

200

770 reads

7. Chauffeur Knowledge

Nobel physicist Max Planck gave speech so often that his driver could recite it. He did one day, while Planck, wearing a driver's hat, sit with audience. Came a question the driver couldn’t answer, he pointed at Planck, “Such a simple question! My chauffeur will answer it!” People run under this thinking fallacy confuse the credibility of the message with the messenger. Warren Buffett counters this bias by investing only within what he calls his “circle of competence” – his awareness of what he knows &does not know. Real scholars see their limits, while pundits spin smoke-and-mirror theories.

205

796 reads

8. Illusion of Control

A man wearing a red hat arrives at the city center every day at 9:00 a.m. and wildly waves his hat for five minutes. One day, a police officer asks what he’s doing. “I’m keeping the giraffes away,” he replies. “There aren’t any giraffes here,” the officer states. “Then I must be doing a good job,” responds the man. Like the red-hat guy, people take credit for influencing situations where they have little control. They pick lottery numbers because they believe they have a better chance of winning that way than with numbers the machine randomly assigns.

203

725 reads

8. Illusion of Control (contd)

The illusion of control makes humans feel better. This is why “placebo buttons” work. People push a button at an intersection and wait patiently for a “walk” sign, even if the button is not connected to the signal. Ditch your red hat by differentiating between the things you can control and those you cannot.

198

701 reads

9. Outcome Bias

Outcome bias, or “historian error,” is the tendency to evaluate decisions based on results, not processes. For example, in retrospect, it’s clear that the US should have evacuated Pearl Harbor before the Japan attacked. Decision to stay seems deplorable in light of today’s knowledge. Yet military higher-ups at the time had to decide amid contradictory signals. A bad result does not necessarily mean the decision was poor. Luck, timing and other external factors come into play. Avoid this bias by focusing on the process and data available at the time rather than concentrating solely on results.

206

644 reads

10. Loss Aversion

Finding $100 would make you happy, but that happiness wouldn’t equal the distress you’d feel if you lost $100. The negative hit from a loss is stronger than the positive hit of a comparable gain; loss aversion explains why investors ignore paper losses and hold falling stocks. Marketers exploit loss aversion to sell. For example, persuading to buy stuffs by describing how much money they’ll lose without it is easier than getting them to buy it by showing the savings they’ll gain. This fear causes people to stay in their comfort zones with investments, personal risks and purchases.

206

618 reads

11. Alternative Blindness

Humans don’t think about all their alternatives when they contemplate an offer. Say that a city planning commission proposes building a sports arena on an empty lot. Supporters make the case that the arena would create jobs and generate revenue. They ask voters to decide between a vacant lot and an arena, but they don’t mention other options, like building a school. Making informed decisions means letting go of either-or choices. Ironically, modern people suffer from too many options. That’s the “paradox of choice.”

203

673 reads

12. Déformation Professionnelle

Mark Twain famously quipped, “If your only tool is a hammer, all your problems will be nails.” This statement beautifully encapsulates this false reasoning habit. People want to solve problems with the skills they have. A surgeon will recommend surgery not acupuncture. Generals opt for military engagement not diplomacy. The downside is that people sometimes use the wrong tools to try to solve problems. Check your toolbox for the right gear and the right cognitive framework.

207

721 reads

IDEAS CURATED BY

CURATOR'S NOTE

Dobelli shared some common thinking mistakes. Knowing these errors won’t help you avoid them completely, but it will help you make better decisions – or at least teach you where you slipped.

“

Curious about different takes? Check out our The Art of Thinking Clearly Summary book page to explore multiple unique summaries written by Deepstash users.

Benny Herlambang's ideas are part of this journey:

Learn more about books with this collection

How to make good decisions

How to manage work stress

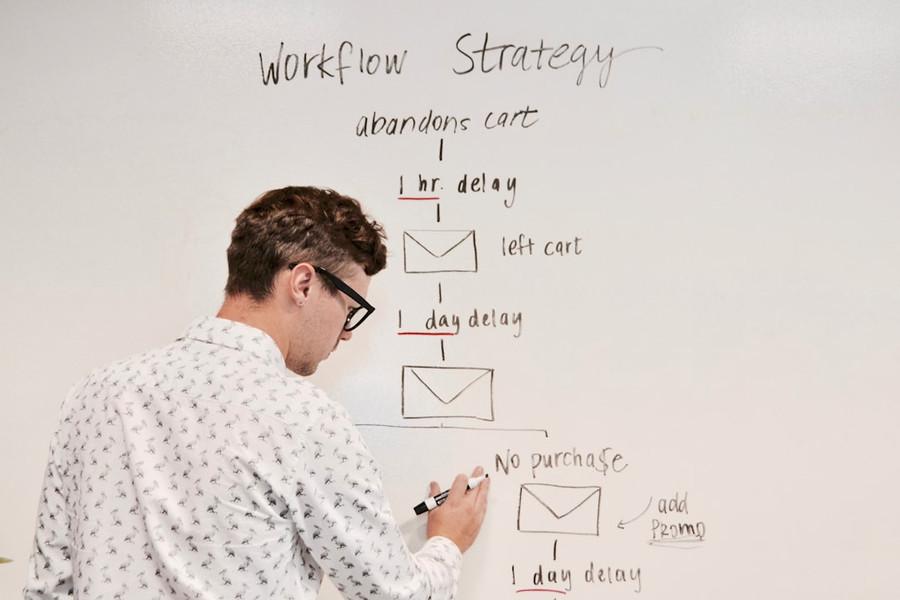

How to manage email effectively

Related collections

Different Perspectives Curated by Others from The Art of Thinking Clearly

Curious about different takes? Check out our book page to explore multiple unique summaries written by Deepstash curators:

6 ideas

5 ideas

6 ideas

Discover Key Ideas from Books on Similar Topics

20 ideas

Predictably Irrational

Dan Ariely

2 ideas

6 Common Decision-Making Blunders That Could Kill Your Business

entrepreneur.com

10 ideas

Why We Make Mistakes

Joseph T. Hallinan

Read & Learn

20x Faster

without

deepstash

with

deepstash

with

deepstash

Personalized microlearning

—

100+ Learning Journeys

—

Access to 200,000+ ideas

—

Access to the mobile app

—

Unlimited idea saving

—

—

Unlimited history

—

—

Unlimited listening to ideas

—

—

Downloading & offline access

—

—

Supercharge your mind with one idea per day

Enter your email and spend 1 minute every day to learn something new.

I agree to receive email updates